GENERATED TITLE: The Mars Canal Mania: A Cautionary Tale for UFO Hysteria

The Martian Mirage: Data Points of Delusion

The late 19th-century obsession with Martian canals offers a surprisingly relevant case study for understanding our current fascination with UFOs. The New York Times, in 2017, confirmed a secret Pentagon program (AATIP) investigating UAPs, and since then, we've seen videos, images, and claims of reverse-engineered extraterrestrial tech. Half of Americans believe in intelligent alien life, yet the reaction is…muted. Why aren't we rioting in the streets? The Mars canal story provides some clues.

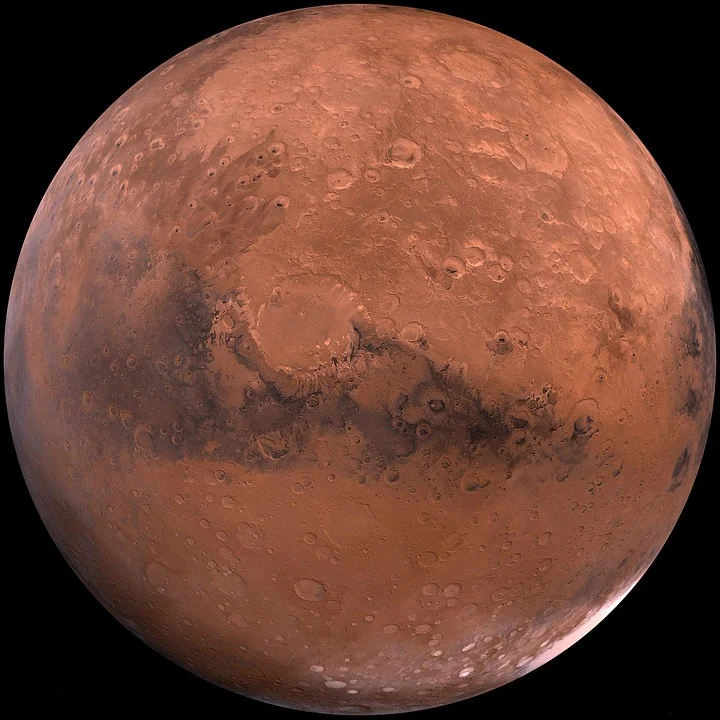

In 1877, a close approach of Mars sparked intense scientific and public interest. Giovanni Schiaparelli, an Italian astronomer, mapped what he called "canali" (channels) on the Martian surface. The English translation as "canals" implied artificial construction, igniting the popular imagination. William Pickering, an astronomer at Harvard, further fueled the fire, reporting vivid details of Martian environments to The New York Herald. The newspaper amplified these descriptions, turning Pickering into an explorer discovering a new world.

Edward Holden, director of the Lick Observatory, initially skeptical, later claimed to have confirmed the "germination" (duplication) of the canals, further validating their existence in the public eye. Percival Lowell, heir to a textile fortune, then built an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, dedicated to studying Mars. He mapped over 400 canals, claiming they were part of a planet-wide irrigation system built by an advanced civilization to survive a drying planet.

Lowell's books became bestsellers, and the public was captivated. People believed they could see the canals with small telescopes. Of course, later exploration proved the canals were an illusion, caused by dust storms and other natural phenomena. Lowell, now often seen as misguided, but his theory stimulated enduring thought and cultural impact.

The "discovery" of Martian canals reveals two key assumptions about alien encounters. First, that discovery is a straightforward process of scientific proof and transparent reporting. The Mars canal mania was a product of the era's mass media, imperial expansion, and environmental anxieties. Pickering's observations, though possibly dubious, were amplified by a newspaper eager for a sensational story. Holden, initially skeptical, changed his tune to maintain his observatory's reputation. This suggests that "scientific" discoveries are often shaped by external pressures, not just objective data. As explored in In the late 1800s alien ‘engineers’ altered our world forever, the late 1800s saw a surge in theories about alien influence on Earth.

Second, there's the assumption that alien discovery would destabilize society. While there was some unease, public order remained largely intact. News about politics, economics, and impending war overshadowed the Martian canals. The public's reaction wasn't the mass panic predicted by science fiction.

UAPs Today: Echoes of the Past, Drones of the Future

Fast forward to today's UAP reports. We see similar patterns. The spread of social media and the commercialization of drone technology have created fertile ground for conspiracy theories and misinterpretations. The videos of "Tic Tac" shaped craft, for example, are compelling, but lack the rigorous analysis needed to rule out terrestrial explanations (drones, atmospheric phenomena, etc.). The military officers claiming reverse-engineered alien technology echo Lowell's confident pronouncements about Martian canals (though with far less observational data, I might add).

The public's muted response to UAP reports isn't necessarily apathy. It might reflect a healthy skepticism, born from past experiences like the Mars canal fiasco. It also highlights the relative importance of alien encounters compared to more pressing concerns like economic inequality, political polarization, and climate change. These are tangible problems with immediate consequences, while the existence and intentions of extraterrestrial civilizations remain speculative.

The article mentions Nikola Tesla hearing a repeating radio signal in 1899 that he thought came from another world, but was likely from Jupiter. This is a classic example of mistaking natural phenomena for alien communication. How many of today's UAP sightings are simply misidentified objects or misinterpreted data, amplified by social media algorithms and confirmation bias?

The lesson here isn't that we should dismiss UAP reports entirely. It's that we should approach them with a critical eye, demanding rigorous evidence and considering alternative explanations. The Mars canal mania reminds us that scientific "discoveries" are often shaped by cultural, economic, and political forces, and that public perception can be easily swayed by sensationalism and speculation. It's easy to believe, and hard to know.